Harnessing Knowledge to Ensure Quality

In establishing Wacker Chemie Nederland B.V. – our first non-German subsidiary – in 1972, we laid the foundation for tapping European markets. Now, over 40 years later, we have no hesitation in calling Europe our home market, where we are the leader in silicon chemistry and ethylene-based polymer products – a position we intend to keep in the future.

The key lies in the high quality of our products, the development of innovative applications and our excellent service. These factors set us apart from our competitors and enable us to add value for our customers. With Germany as the backbone of our global production network, we manufacture around 80 percent of our products in Europe, and sell them throughout the world.

This annual report relates four stories that illustrate the strategies and ideas that we use every day to consolidate and expand our strong market position in Europe, the stable foundation for our global business.

With surgical precision, eight gigantic tunnel-boring machines cut through the bowels of London, weaving between sewers and gas pipes, foundation piles and subway shafts. They must not deviate by more than a millimeter from the planned route. Yet even if they remain within this tolerance, they still sometimes pass within less than a meter of the arteries of this megacity.

Crossrail, Europe’s biggest infrastructure project, employs some 10,000 people. A new west-east rail link is being built through the center of London at a cost of £15 billion, requiring some 42 kilometers of tunnel to be dug. The link is not planned to open until late 2018, but investors are already developing major property projects close to the ten new train stations.

The future of Europe is being built here beneath the streets of London. Leading economic research institutes would welcome more such projects in Europe, as the continent is recovering only sluggishly from the financial and sovereign-debt crisis. In 2014, for the first time in two years, the European economy started to grow again, albeit at a slow pace. Many countries are still struggling with high unemployment, heavy debt and low levels of investment. In France and Italy, two of Europe’s major economies, growth is further hampered by the need for reform. Both the European Central Bank and many politicians in Brussels are demanding more investment in research, education and infrastructure to put the European economy back on track. After all, economics is 50 percent psychology, and Europe has an attitude problem: there’s a lack of confidence in a strong recovery.

Particularly in Southern Europe, consumers are putting off purchases since they assume that products will continue to fall in price, with the threat of deflation. In addition, the rate at which European companies are investing has fallen. In 2007, they reinvested 24.7 percent of their profits. Since the financial and sovereign-debt crisis of 2008, this figure has dropped to between 21 and 22 percent.

Refocusing on Industry

Against this backdrop, Europe is once again focusing on the importance of its industry. The declared aim of the European Commission is for industry to contribute 20 percent to GDP by 2020. At present, it is less than 15 percent, with major differences between regions. In Germany, industry makes up 22 percent of GDP, contrasting with only 10 percent in the UK. But industry accounts for over 80 percent of EU exports, and private-sector research and innovations. Every additional job in manufacturing creates up to two jobs in other sectors. The EU has introduced measures to provide for cheaper and easier access to energy, raw materials and credit.

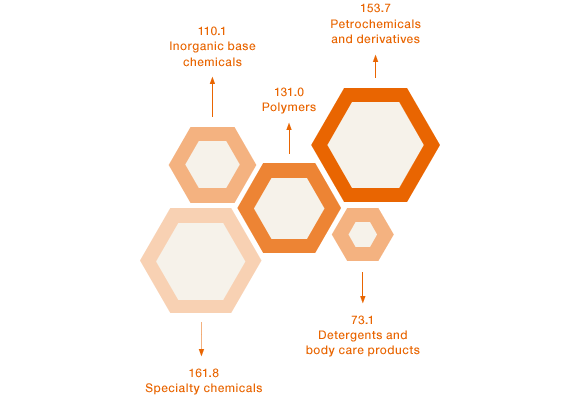

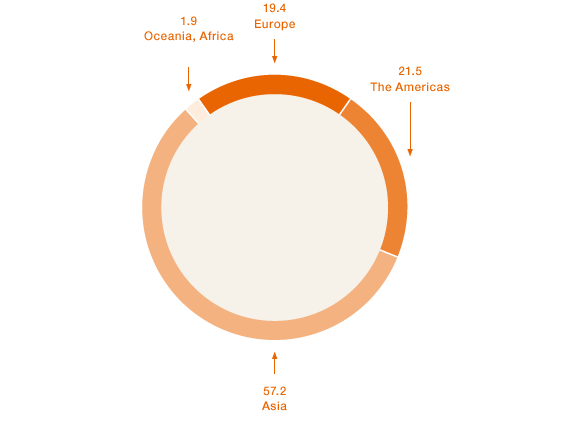

Global R&D Expenditure in the Chemical Industry

Source: VCI-Oxford Economics Study, 2014

This will benefit the chemical sector, a key European industry. Almost three-quarters of total chemical production remains within the European internal market. And without chemicals, the Crossrail tunnel builders wouldn’t get very far. The tunnel boring machines treat the soil with polymers and surfactants to make excavation faster and safer. The many thousands of reinforced concrete rings that line the tunnel contain additives to make them durable and fire resistant. “With its large range of products and innovative solutions, the chemical industry is making an important contribution to the prosperity of the EU economy as a whole,” says Kurt Bock, CEO of BASF and former president of the European Chemical Industry Council (Cefic).

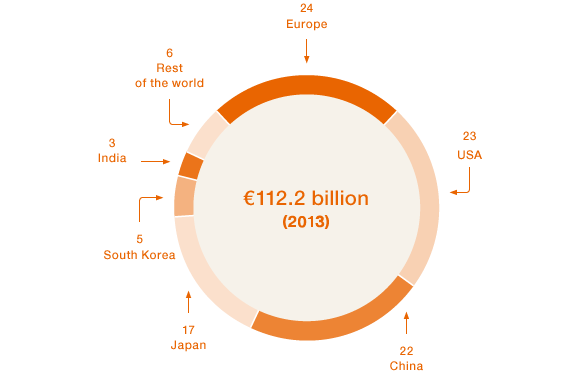

The chemical industry has achieved a positive trade surplus every year for the past ten years. The record year was 2013, when it reached € 49 billion. The trend can be attributed mainly to the growth of the emerging economies. Some 85 percent of exports were for specialty chemicals and chemicals for consumer products. The main beneficiaries of this trend are German companies, which are responsible for over a quarter of chemical production in the EU. On an international scale, Germany is the fourth biggest chemical producer, behind China, the US and Japan. With sales of about € 190 billion, chemicals are the third biggest industry in Germany, behind the automotive sector (€ 364 billion) and machinery construction (€ 223 billion).

Energy Costs as a Brake on Growth

At first glance, it seems paradoxical that, though the German chemical industry is an export champion and the European chemical industry has almost doubled its revenue in the last 20 years, Europe’s share of the global market has dropped – from 35.2 to 17.8 percent. Why? The emerging markets have seen their share of global chemical sales more than triple in the past 20 years – from € 1,300 billion to € 4,100 billion. Europe was unable to benefit from this growth as much as it could have, according to the 2013/2014 Cefic sustainability report: “The decreasing extra-EU export market share is mainly due to declining competitiveness, resulting amongst others from high energy and feedstock prices. This affects particularly the European petrochemicals and polymers sector. The petrochemical sector currently provides the starting point for almost all value chains in the chemical industry.”

The European chemical industry does profit from cheap crude oil: its price fell by 40 percent to a five-year low between June and December, and the IMF predicts this will result in growth in the global economy of 0.8 percent in 2015. However, one main cause of the price drop – the fracking revolution in the US – also poses a big problem for the European process industry: America is flooding its economy with shale oil and gas; production has increased by three million barrels a day to 8.5 million barrels since 2010 – thereby triggering a new wave of reindustrialization. According to the IMF, US exports have grown by 6 percent as a result.

The European Union, on the other hand, has only 1 percent of global oil and gas reserves. Annual imports in 2013 are estimated to have been about € 400 billion. Added to this are costs for the energy transition. German companies pay about two times as much for their electricity as their US competitors. Germany’s EEG levy costs the chemical industry € 1 billion per year.

New chemical plants to the tune of over $ 100 billion will have been built in the US by 2016, solely due to low energy prices. In Germany, by contrast, investments are below the level of depreciation. The German Chemical Industry Association (VCI) considers it an alarm signal for competitiveness that in 2012, for the first time in many years, the industry’s foreign investment exceeded its domestic investment spending by over € 1.4 billion.

Innovation Is the Key to Europe’s Future Success

The only way that resource-poor Europe can remain competitive is through a wealth of innovation. Manufacturers often profit from ideas and applications created by the chemical industry. Automotive manufacturers are particularly resourceful in this respect. According to the Center of Automotive Management (CAM), innovations reached a record level of 1,010 in 2013. 41 percent of those were accounted for by only three companies: BMW, Daimler and Volkswagen. Most innovations were improvements in fuel consumption, alternative drives and digitalization of vehicles, such as driver assistance systems. These developments were supported by the chemical industry with, for example, innovative, weight-saving polymers or the base materials for making more efficient batteries and electronics. Even the energy transition would not be possible without the chemical industry. The increase in the performance of wind turbines from, on average, 164 kilowatts in 1990 to over 7 megawatts for modern high-performance wind parks is the result of a large number of new developments. Chemists have developed resins and curing agents, lubricants, flow improvers and new ultra-lightweight materials for turbine towers and rotors.

Besides its inventiveness, Europe can also rely on growth in the countries that joined the EU in 2004, most of them Eastern European. In the first five years of their membership, the economies of the ten new member states grew by 23 percent, compared to only 8 percent in the old EU states. Poland, in particular, with its population of almost 40 million, has undergone an astonishing boom. Even during the global financial crisis, the Polish economy was the only one in Europe to grow, with a growth rate of about 3 percent in 2014. The World Bank predicts a doubling of Polish economic output in the next 15 years. Besides successful structural reforms, “low pay and the high work ethic of its workers” are the main drivers of the country’s success, says The Economist. For instance, Volkswagen constructs 155,000 cars per year In the Polish city of Poznań, MAN manufactures trucks and buses, while Hugo Boss produces shoes there. In the medium term, however, Poland could be much more than the “extended workbench” of European supply chains, says Jerzy Langer, a physicist and the chairman of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT) in Wroclaw, which brings together companies and researchers particularly in the fields of nanotechnology and biotechnology. “Germany used some of its Marshall Plan funds to build innovative, international companies after the Second World War,” writes The Economist. “Poland could be doing the same with EU funds.”

The conflict between Ukraine and Russia is dampening growth in Eastern Europe. For instance, overall trade with Russia fell by a fifth in 2014, according to the Association of German Chambers of Industry and Commerce (DIHK).

Investment Program for Europe

However, drastically falling energy prices could turn into a huge economic recovery plan. According to an analysis by UniCredit, companies and consumers would benefit to the tune of € 35 billion, around 1 percent of GDP. Quite apart from the turbulence on the oil market, Europe has recognized that a strict austerity policy can be damaging in the long term. The EU Commission therefore wants to boost the economy in 2015 with its “Invest in Europe” program. Its idea is that there are sufficient funds available globally – now more of them should find their way into the European economy. The European Investment Bank is providing around € 20 billion in funds to guarantee high-risk investments and loans that have passed a rigorous vetting process. In this way, private investors are to be encouraged to get involved in digital, energy and infrastructure projects, leading to overall investments of about € 300 billion.

The Biggest Chemical Companies in Europe

|

|

||||||||

|

Sales in US$ million |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

||||||||

|

1 |

BASF |

101,906 |

|

32 |

Solvay |

13,691 |

||

|

… |

|

|

|

… |

|

|

||

|

6 |

LyondellBasell Industries |

44,062 |

|

34 |

DSM |

13,250 |

||

|

7 |

Shell |

42,279 |

|

… |

|

|

||

|

… |

|

|

|

38 |

LANXESS |

11,434 |

||

|

10 |

Bayer |

29,251 |

|

… |

|

|

||

|

11 |

INEOS |

27,864 |

|

40 |

Borealis |

11,220 |

||

|

12 |

Total |

25,743 |

|

41 |

Henkel Adhesive Techn. |

11,182 |

||

|

13 |

Linde Group |

22,944 |

|

… |

|

|

||

|

… |

|

|

|

50 |

BP |

8,628 |

||

|

16 |

Air Liquide |

20,974 |

|

… |

|

|

||

|

17 |

AkzoNobel |

20,099 |

|

52 |

Arkema |

8,401 |

||

|

18 |

Johnson Matthey |

18,598 |

|

… |

|

|

||

|

… |

|

|

|

54 |

Versalis |

8,071 |

||

|

20 |

Evonik |

17,735 |

|

55 |

Styrolution |

7,990 |

||

|

… |

|

|

|

… |

|

|

||

|

28 |

Merck Group |

14,741 |

|

65 |

Clariant |

6,822 |

||

|

29 |

Syngenta |

14,668 |

|

… |

|

|

||

|

… |

|

|

|

70 |

PKN Orlen |

6,433 |

||

|

31 |

Yara International |

13,950 |

|

… |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

74 |

WACKER |

6,170 |

||

Yet according to some, for example Michael Hüther, head of the Cologne Institute for Economic Research (IW), the success of the European project ultimately lies in striking the right balance between integration and national sovereignty. He goes on to warn against political union: “Europe relies on the self-confidence of its nations and on the ability of its nation states to act.” Despite rapid globalization, European countries will remain each other’s most important trading partners in the long term. About two-thirds of European trade takes place in the internal-European market. For Cefic, the strength of the chemical industry “comes from full and efficient integration of production across Europe.” Michael Hüther, too, considers it constructive to develop Europe along shared supply chains. “But,” he says, “we don’t need to create a federation to do so.” Regardless of the pace at which Europe pursues political integration – one thing seems certain: to survive in an ever-more competitive world, Europe’s only choice is to intensify economic cooperation.

When, in December 1954, German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer announced his government’s strategy of Western integration, he was concerned with security, peace and freedom – values that are essential for any economic engagement to thrive. Sixty years after Adenauer’s speech, his sober words still hold true: “The unity of Europe was a dream of a few. It became a hope for many. It is a necessity for us all.”