Tennessee – High-Tech in the Countryside

There are three reasons why the new polysilicon plant in the US state of Tennessee is a historic milestone for WACKER. First, it is the biggest single investment thus far in the history of the company, which recently celebrated its centennial. Second, the new site signals a clear commitment to North America, a key region for WACKER alongside Europe and Asia. Third, the greenfield plant, which will employ some 650 workers, is one of the most modern facilities worldwide for the manufacture of hyperpure polysilicon, a base material for high-efficiency photovoltaic systems. The Charleston plant will enable WACKER to maintain its customary standard of high quality, reliably providing polysilicon to meet growing international demand for many years to come. Gradually, the site will become a fully integrated production plant. In order to achieve this, the project team members and technical experts, along with production employees, engaged in a close transatlantic dialogue right from the word “go.”

The Americas

High-Tech in the Countryside

There are three reasons why the new polysilicon plant in the US state of Tennessee is a historic milestone for WACKER. First, it is the biggest single investment thus far in the history of the company, which recently celebrated its centennial. Second, the new site signals a clear commitment to North America, a key region for WACKER alongside Europe and Asia. Third, the greenfield plant, which will employ some 650 workers, is one of the most modern facilities worldwide for the manufacture of hyperpure polysilicon, a base material for high-efficiency photovoltaic systems. The Charleston plant will enable WACKER to maintain its customary standard of high quality, reliably providing polysilicon to meet growing international demand for many years to come. Gradually, the site will become a fully integrated production plant. In order to achieve this, the project team members and technical experts, along with production employees, engaged in a close transatlantic dialogue right from the word “go.”

Product

Polysilicon

Capacity

Over 20,000 metric tons p. a.

Undeveloped Area

2,226,000 m2

As you drive along the winding country roads of eastern Tennessee, past typical American farms with their large round silos, you hardly expect to encounter such a large-scale industrial site around the next bend. Where the Hiwassee River snakes its way through the green, hilly countryside and the tiny town of Charleston (official population: 651) is nestled, Wacker Chemie AG’s newest plant suddenly comes into view.

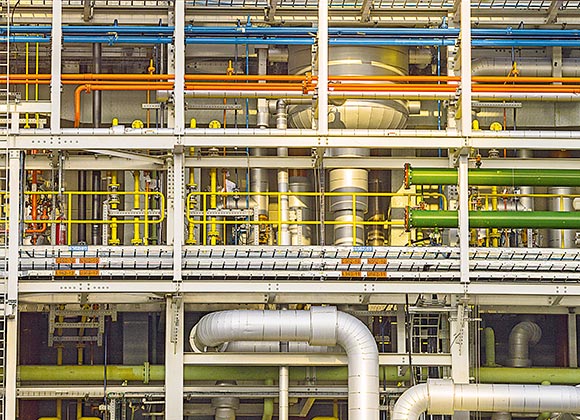

A High Level of Complexity

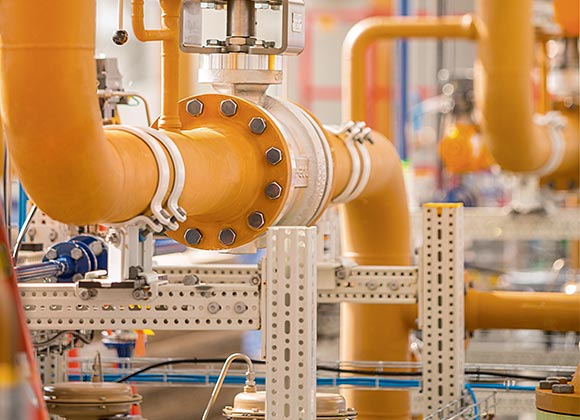

A row of distillation columns, some of them over 60 meters high, sparkle in the sunshine, flanked on one side by a seven-story building for the manufacture of trichlorosilane and, on the other, by a deposition hall. These distinctive structures are only three out of a total 34 buildings on the 550-acre site; since ground was first broken in early 2011, WACKER has transformed the site from simple farmland into the world’s most cutting-edge plant for the production of hyperpure polysilicon.

Known inside the company as Poly 11, the plant is a major project. At the peak of construction, over 3,500 workers from more than 140 contractors were on the building site. A total of 237,500 flatbed trailers moved 2.9 million cubic meters of earth. Some 111,000 cubic meters of concrete was poured and over 40,000 metric tons of steel used. WACKER and its partners installed around 100,000 instruments and valves.

“The site’s daily progress was extraordinary, and it was very exciting to witness this impressive plant ramp-up firsthand,” says site manager Dr. Konrad Bachhuber, who has supervised the project since December 2011. A doctor of chemistry, he has worked for WACKER for 26 years. During that time, he has handled several major projects in Germany and China, but Charleston was bigger than anything he’d ever experienced. “To build a plant of this complexity on a greenfield site is a once-in-a-lifetime experience,” says Bachhuber.

At around US$ 2.5 billion, Charleston is not just WACKER’s single biggest investment to date. In more ways than one, WACKER has entered uncharted territory with this project. It is not only the first time that the company has built an entirely new polysilicon plant on a greenfield site instead of expanding an existing site’s infrastructure. It is also WACKER’s first major production site for polysilicon in North America, where the underlying conditions are in many ways quite different from those in Germany: different building regulations and approval procedures, for instance, different approaches to finding qualified workers, and cultural differences such as the way people interact in the workplace. As Bachhuber sums up: “We have had five very intensive years in Tennessee. During this time, both sides learned a lot from each other. There were many things we could not simply apply unchanged from Germany, and we had to find new partners who understood our requirements, and were able to fulfill them.”

The result is a plant that is a model for the efficient manufacture of high-quality polysilicon. The process in Charleston is the same as in the existing plants at Burghausen and Nünchritz in Germany: silicon metal is undergoes a chemical reaction with hydrogen chloride to make trichlorosilane, which is subsequently purified in the distillation columns before the hyperpure polysilicon is deposited on rods in the deposition reactors. Crushed and packed, the polysilicon is delivered to solar and semiconductor-wafer manufacturers. “Our product is so perfect that impurities are measured in no more than parts per trillion,” explains Bachhuber. “That’s the same as a single typing error in 1,000,000 books of 1,000 pages each.”

Charleston is designed to be able to manufacture over 20,000 metric tons of polysilicon a year when running at full capacity and, according to WACKER’s own plans, the plant will account for at least around one-quarter of the company’s total production in 2017. “Solar power and semiconductors are megatrends. We are taking a long-term approach and building up the capacity to serve this international market,” says Bachhuber.

Newly installed photovoltaic capacity rose by another 20 percent last year to reach some 55 gigawatts, and experts are expecting a further increase to around 65 gigawatts in 2016. This enormous growth is driving down the system costs of solar installations even further. In many countries, photovoltaic systems have now reached cost parity with gas-fired power plants – the success of solar power is becoming a global phenomenon. The USA, China, Japan and India have now overtaken Europe as the main markets for PV systems. But in many other markets, too, projects to tap the sun’s capacity as an extremely low-cost, virtually inexhaustible source of clean energy are sprouting up everywhere.

That means that demand for polysilicon is likely to continue growing strongly. WACKER will be prepared to meet this demand, as the Charleston site – like Nünchritz and Burghausen – offers sufficient space to expand polysilicon production capacity if needed; the site has long-term potential to become a fully integrated silicon site. Such a site would include the production of pyrogenic silica, which can be used to adjust the viscosity of paints and adhesives, and perhaps even silicones at a later stage.

“Eastern Tennessee is an ideal location for this,” explains Gary Farlow, President & CEO of the Chamber of Commerce of Cleveland / Bradley County, where the new plant is located. “WACKER really did its homework before making the single biggest private-sector investment in Tennessee’s history right here in our county.” Two power plants of the publicly owned Tennessee Valley Authority supply the plant with reliable, low-cost electricity. The nearby river provides cooling water as well as one of several means of transport. After shipment from Europe, the distillation columns were transported to near the site by river barge. Charleston offers excellent access to several highways, another option for the transportation of raw materials and finished polysilicon.

What is more, says Farlow, the local governments and the state of Tennessee have cooperated closely with WACKER from the outset to train workers for the 650 new jobs created at the plant. “Providing 650 new jobs is important in itself. But it is even more important that the new jobs are both challenging and well-paid,” says Farlow. “WACKER’s project will have a positive long-term effect on the entire economy of the region. The plant may even be the seed for a solar energy cluster.”

Tailored Training Facility

One result of this close collaboration, and one that has earned acclaim across the country, is the WACKER INSTITUTE, a tailored educational institution the company developed in partnership with Chattanooga State Community College. It has taken the model that has been tried and tested at the Burghausen Vocational Training Center since 1969 and, in a manner of speaking, exported it to Tennessee. “The WACKER INSTITUTE has been a resounding success,” says Dr. George Graham, who has been head of the institute since January 2012 and a WACKER employee since June 2014. “What we have created here in the record time of six months differs fundamentally from the traditional American vocational training system, in which apprenticeships are not as common.”

The WACKER INSTITUTE is located on the college campus, in a dedicated building in which the state of Tennessee, the local government and the company invested a total of US$ 13 million. Since fall 2011, around 200 students have been trained there as chemical technicians or electrical & instrumentation technicians, and WACKER has already employed 110 of them. “Anyone completing their training here is given first consideration by WACKER. This offers the people in the local region excellent prospects of finding jobs that are challenging and secure,” says Graham. “I wish this practical vocational training model would be replicated elsewhere.” For its outstanding achievements, the WACKER INSTITUTE was honored in 2013 with the Bellwether Award for the best worker training program in the entire USA.

The five distillation columns are a distinctive feature of the new production site. It is in these columns that the starting materials for polysilicon production are purified to semiconductor grade.

An Equal Partner

“Without the institute, we would never have managed to meet our demand for personnel,” says Erika Burk, head of Human Resources at WACKER in Charleston. “We do not see the Community College as a service provider, but rather as an equal partner, who provides us with extremely valuable input.” Burk became the planned plant’s first employee in December 2010. Initially, she searched for suitable workers, making calls on her cellphone and using the wireless LAN in local cafés – all months before the first excavators rolled onto the site. In her first year of employment, she and her staff sifted through some 10,000 applications and chose 53 from 4,200 candidates to start training as chemical operators.

In her opinion, the WACKER INSTITUTE has not only acted as a magnet for talented workers within a 100-mile radius, but also raised the German company’s profile among the population. “We wanted to become an attractive employer, one that offers people careers and not just jobs,” says Burk. “And we’ve succeeded. People understand that we take the long view and they respect that.”

Shervon Frazier agrees. She began working for WACKER in July 2011, as an assistant to the engineering and construction team, and watched an ultramodern plant grow before her eyes from the office in which she worked. “We were something akin to the first settlers. Anyone who had anything to do with the project came through us,” says Frazier, who at peak times managed temporary offices for approximately 400 employees. “It fills me with immense pride every day to be a part of this team.”

Aaron Franckhauser is equally enthusiastic. A WACKER employee from the neighboring town of Cleveland, he was among the initial intake of 53 students. “It was important to me that WACKER placed so much emphasis on good training. I’m also interested in the renewable energy sector.” So, starting June 2011, Franckhauser attended classes for six months at the WACKER INSTITUTE before spending another six months at the Burghausen plant in Germany. He has been part of the Infrastructure Team in Charleston since August 2012.

“As we are the company’s own utility, we were the first to go on stream – with heating and cooling, water and wastewater, and chemicals such as chlorine gas, hydrogen, caustic soda and nitrogen,” says Franckhauser, describing his job. With hindsight, he sees the fact that commissioning of the plant was delayed by 18 months due to rescheduling as an unexpected opportunity to improve his qualifications. “We were flexible enough to take on other tasks at the plant.” These included safety tests, learning how to safely work with chemicals and handling aspects of building inspections. “I now know every tool that I’ll be working with inside out,” says Franckhauser.

Dan King, who began setting up the plant fire department in January 2013, is similarly proud. After 19 years as a deputy fire chief in Harriman City, some 60 miles from Charleston, the new job at the WACKER plant was, in his own words, “the challenge of my career.”

As plant fire departments are a rarity in the USA, he consulted closely with his new colleagues in Germany and sought the advice of experts at Texas A&M University. “WACKER is very serious about safety, which is why I had all the resources at my disposal to put an all-star team together,” he says. He now leads a team of 31 firefighters. King is particularly proud of one thing: the fire department badge, which is emblazoned with five shining distillation columns. All the members of his team wear it on their sleeves. “I designed the badge even before I’d interviewed the first applicants for the team,” he says. “For one simple reason: it is the embodiment of everything WACKER stands for in Tennessee.”